UNIT 1: THEORIES, POLICIES & PRACTICES

(UNIT 2: INCLUSIVE PRACTICES CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK! )

Course Leader & Senior Lecturer / MA Commercial Photography, LCC

I am a photographer, photo director, and educator, currently serving as Course Leader & Senior Lecturer of the MA Commercial Photography program at LCC. We have just welcomed our third cohort to this relatively new 15-month program, and I have recently welcomed my second son. He just turned one and is now enjoying nursery.

I am excited to return to LCC after maternity leave and resume my role as Course Leader while simultaneously pursuing the PGCert. I hope to develop empathetic and effective ways to enhance the learning experience for our diverse cohort, as well as explore new and efficient strategies for structuring dynamic up-to-date pedagogy.

February 2025

Reflection 1: Putting the PCSA to Use

In my first PGCert tutorial, I learned about an exciting and supportive UAL policy that I hadn’t heard about through UAL comms (possibly due to being on maternity leave): the PCSA, or Parental Carer Support Agreement. This policy allows for a two-week extension on unit submissions (similar to an ISA), along with other tailored support measures based on the applicant’s needs. As a parent of two young children, I decided to apply for this in relation to my PGCert. I met with a representative from the Student Health team, and together we drafted a version of the PCSA that would best support my situation. It has been incredibly helpful in supporting my engagement with the PGCert. Because I was on maternity leave, the remission I was entitled to had not been applied for (as I wasn’t around the summer before starting the PGCert). Although my Programme Director kindly offered me some additional hours, it was only a fraction of what I should have received. Without the PCSA, I would not have been able to complete this unit.

I have also signposted the policy to a couple of MACP students who have young children of their own. They are now making use of it, and it has had a dramatic impact on their connection to the MA Commercial Photography course. It has really boosted their sense of being supported not just by the course team, but by LCC and UAL as a whole.

In Bolt-holes and breathing spaces in the system: On forms of academic resistance (or, can the university be a site of utopian possibility), Darren Webb reflects on the transformative potential of academic resistance and solidarity through the concept of hapticality:

“Hapticality describes a way of feeling that is at once unsettled, ‘to feel at home with the homeless, at ease with the fugitive, at peace with the pursued,’ and intensely intimate, ‘the capacity to feel through others, for others to feel through you, for you to feel them feeling you’” (Webb, 2018, p. 103).

For these students, and for myself, the PCSA has created this kind of hapticality – an empathetic, embodied recognition of the complexity of our lives within academic systems.

The Photography department at LCC was previously unaware of the policy, but they are now actively signposting students to it. Across the photography programme, we are now including PCSA deadlines (alongside ISA ones) in all assignment briefs. Learning about this policy through the PGCert has had a genuinely transformative impact on my course, our department, and the student community. I plan to feed this back to the Student Health team and also ask them to make the policy easier to find on the UAL website – as it is a little tricky to find. I will also be encouraging them to reiterate this fantastic support in future communication to the student body.

Reflection 2: OBL Online Reading

For the first reading of Workshop 1, I was assigned Willcocks and Mahon’s article The potential of online object-based learning activities to support the teaching of intersectional environmentalism in art and design higher education, published in Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 22(2), pp. 187–207 (Willcocks and Mahon, 2023). In the text, they explore the effectiveness of online object-based learning (OBL) through the teaching of intersectional environmentalism at Central Saint Martins (CSM). The study focuses on the Colonialism to Climate Crisis event, a collaborative unit at CSM, University of the Arts London (UAL). The event aimed to highlight the links between colonialism and environmental exploitation, using 18th and 19th century botanical illustrations.

The study found that online object-based learning helped students critically engage with the historical connections between colonialism and climate change. Students appeared to recognise that the colonial extraction of natural resources contributed to present-day environmental injustices, with one noting: “This event really opened my eyes in seeing how much colonialism destroyed nature and how nature answers back” (Willcocks and Mahon, 2023, p. 199). I was personally very interested in what Colonialism to Climate Crisis achieved in terms of opening up students’ minds. Working with early photographic techniques myself, I hadn’t previously considered the colonial implications of these processes until delving deeper into them.

Regarding the potential of online OBL, the study identified both benefits and challenges. Students appreciated the interactive tools used – maps and Padlet discussions for example – which helped to make abstract issues more tangible in a digital space. Some students found digital learning more accessible, while others struggled with disconnection and fatigue. One participant noted: “Face-to-face contact, body language, lip reading, is so important for communication, and it’s lost in online learning” (Willcocks and Mahon, 2023, p. 199).

I think it is important to note that the study took place during the pandemic, when teaching was forced online. I feel there may be a slight bias in the paper toward concluding that things went well, perhaps due to the necessity of the situation. I was not employed by UAL at that time, but I can only imagine how challenging it must have been to deliver quality education remotely. I’m sure students appreciated any attempt to make their learning as tangible and engaging as possible. There is a valid argument that in-person OBL can limit the number of participants due to space and logistical constraints, whereas online delivery has the potential to reach a wider audience by default. That being said, I do question how deep and immersive the online experience can truly be, especially when the learning involves the physical handling of objects. I would be interested to see how the Colonialism to Climate Crisis event functions in a physical space.

In terms of my own teaching practice, this paper has prompted me to reflect on how object-based learning currently functions in MA Commercial Photography and how its inclusion might be enhanced. I am particularly interested in how our cohort can access relevant archival materials held at UAL – such as the Kubrick Archive at LCC – as well as resources in external institutions like the National Portrait Gallery and the V&A. I am also considering how some of the digital delivery methods highlighted in the Willcocks and Mahon study, such as the use of Padlets to stimulate engagement, could be integrated into our own classroom sessions to enhance interactivity.

While I agree with the statement, “It seems easier for students to get lost online or to simply ‘tune out’ or drop out” (Willcocks and Mahon, 2023, p. 201), I’ve also observed similar disengagement during extended in-person sessions, particularly with larger cohorts. Taking the insights from this paper on board, I am exploring ways to increase student engagement with object-based learning beyond the numerous technical workshops already offered. This includes encouraging in-situ exploration of physical archives and incorporating objects directly into classroom teaching.

Update: We will be taking our students to visit the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Print Room in early June 2025. They will work in groups of 12 (three groups in total) to view and handle historical fashion photography from the V&A collection.

OBL Microteaching Account

Cyanotypes

20 Minute Session Plan

- 6 minutes – lecture slides explaining (in brief) the history and process of cyanotypes, an introduction to Anna Atkins and showing a QR code that allows colleagues to look through the publication ‘British Algae’ via the British Society scanned book collection.

- 2 minutes – hand out cyanotype paper and pressed botanicals, while the students process the inspiration of Anna Atkin’s book.

- 3 minutes – students to design their cyanotypes by placing pressed botanicals on cyanotype paper and adding to the glass frame, for developing on the window ledge

- 7 minutes – cyanotypes to develop while I share the final lecture slides, which include student research into the history of Anna Atkins followed by a discussion about her links to colonisation, and finally share a link to the performative project by Tom Pope and Matthew Bennington which explores this in greater detail.

- 2 minutes – student’s to wash their creations under running water and place on the print dryer

Summary of the Session

Inspired by my first assigned reading in Workshop 1 on object-based learning (Willcocks and Mahon, 2023), which explored the dissemination of botanical illustrations through online OBL, I was struck by the ‘light bulb learning technique’ that the session sparked in students, surrounding the often-hidden agendas behind historical work. I decided to draw on this idea for my own microteaching session, using physical cyanotypes to create a similar kind of revelation.

Alternative photographic processes are an important part of my artistic practice and expertise, though I had never taught cyanotypes before. I usually work with salt prints and photogravure and enjoy passing this knowledge and early understanding of the craft on to my students. Cyanotypes have long been on my list to explore further, and the timing felt right. A recent exhibition by Tom Pope and Matthew Bennington, Almost Nothing but Blue Ground at Forma, reignited my interest, especially in the work of cyanotype pioneer Anna Atkins. Her book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (Atkins, 1843), widely regarded as the first ever photobook, has been on my mind, particularly in light of its colonial links.

I felt this would be a rich and relevant topic for my microteaching session and one I hope to develop into a longer workshop on my course, embedding UAL’s framework for Climate, Social and Racial Justice more deeply into our pedagogy. My main concern was the challenge of fitting too much into a 20-minute session, but I began designing a structure that could serve as a springboard for a longer format with my MA Commercial Photography cohort.

I gave a brief overview of the cyanotype process and Anna Atkins’ role in its development. While I wasn’t able to get hold of a physical copy of her first book (which would have added a valuable object-based layer to the learning), I was pleased to discover that the Royal Society has digitised and archived the book, making it freely accessible online. This linked nicely back to the Willcocks and Mahon reading. I created a QR code so students could access the book via their laptops and browse it for inspiration.

If I were to run this session with my students, I’d follow the reading with a short foraging trip around the local area, encouraging them to gather natural materials to use in their cyanotypes. I’d also guide them through creating their own light-sensitive paper in the darkroom, giving them a better understanding of the chemistry, its organic make-up, and the role of light sensitivity. This would enhance the magic of early photographic discovery. For the purposes of the microteach, I used pre-sensitised (and dried) paper, along with pressed and dried leaves and flowers, to stay within the 20-minute time frame.

After looking through Atkins’ work online, students quickly composed their cyanotypes. I assumed the high UV levels in the tower block would help speed things up, but this part of the session felt rushed and not entirely successful. Feedback confirmed this. They wished they’d had more time to explore the book, reflect, and create. I completely agreed. If run over a three-hour morning or even a full day, each part of the process could be given the time it needs.

I also realised that the windows in the tower block must have a protective UV coating, as the light wasn’t strong enough to develop the prints within the session. I had to stay calm and adjust, allowing the cyanotypes to develop during my colleagues’ sessions instead.

Thankfully, there was still time within the 20 minutes to look into Anna Atkins’ background. While the cyanotypes developed slowly in the window frame, I asked students to research her history and come back with one or two surprising discoveries about her life and the context behind her two cyanotype books, one of which is considered the first ever photography book. They shared their findings and, to my relief, my intention came through clearly. Several students quickly found that Atkins’ husband had ties to the West Indian slave trade, and that some of the botanical samples used in her second book were taken from Jamaica. If we’d had more time, this could have opened up a much deeper group discussion.

At the end of the session, I washed and dried everyone’s cyanotypes so they could take them home. Each student left with a tactile, beautiful object, new to them but embedded with meaning from the session. Something to keep, but also something that asked them to reflect on the context and implications of early photographic work.

Feedback from Tim (Tutor)

Rachel began the day with a 360 ‘immersive’ experience; through all the ‘sensory modalities’ – and teaching methods that integrate learning across senses, thereby stimulating both ‘memorability’ and ‘active learning’! If you want to read up on theories of doing, ‘sensori-motor’ activity, please be my guest. A number of you lit the fuse of ‘active learning’, but let’s start with this ref. here (Advance HE, n.d.) more later…She uses the ‘lecture’, and a type of ‘demonstration’ that was close to ‘discovery learning’ perhaps, where ‘experimenting’ is guaranteed to bring results…if only the sun would shine…?! But it worked! Beautifully allowing the satisfaction of seeing the results of learning in those cyanotypes. The ‘participative’ element allowed us to reference the ‘colonial’ backstory of this form too. Multiple methods can lead to very different experiences and learning within a group, so many paths to follow…Great for ‘synthesis’ and ‘complexity’ in teaching. Wonderful for ‘lateral thinking’ and making connections. Thanks so much for going first and waking up all our brain cells! At once. This was a deeply educational walk in a rich and diverse forest, full of sights, sounds and fascinating interest with a fantastic guide.

Reflections on Feedback

Thank you for your thoughtful and encouraging feedback. I’m really pleased that the immersive, sensory-led approach resonated and stimulated active learning. The balance between lecture, demonstration, and discovery learning was something I aimed to cultivate, so it’s great to hear that this was effective – despite the unpredictability of the sun.

I also appreciate your point about multiple methods leading to different learning experiences. The challenge of timing (and sunshine!) is something I have reflected on, and a longer session would allow deeper engagement with both the practical cyanotype process and to delve into the historical context of Anna Atkins’ work. In a full-length workshop, I’d incorporate more time for discussion, exploration, and experimentation, especially around the colonial implications of early botanical photography and some of the minerals used in early processses.

Your mention of ‘sensorimotor’ activity and its role in learning is intriguing and thank you for the Advance HE reference (Advance HE, n.d). The ideas of ‘lateral thinking’ and ‘synthesis’ align with my goal of making connections across historical and artistic contexts.

Moving forwards, I’d refine the session by:

- Expanding the pre-experiment phase to give students more time to engage with Atkins’ work before creating their cyanotypes.

- Work in the darkroom, so the students can prepare their own paper and while the paper dries…

- Send the students out to forage for their own botanicals.

- Adjust the exposure process to account for light conditions, perhaps incorporating an artificial UV light as a backup.

- Build in more structured discussion around the colonial backstory and its contemporary relevance, linking to the use of salt, silver and gold in other alternative photographic processes.

This session has been a fantastic learning experience for me, and I appreciate your insights on the effectiveness of the teaching strategies used. Thank you for your feedback and for setting such a supportive environment for our microteaching session.

REFLECTION 3: Beyond the ‘Terrors of Performativity’

My teaching philosophy is deeply entwined with my practice as a photographer and my former career as a photo director. Both roles involve the constant negotiation between authenticity and expectation, between creative intuition and external judgment. These tensions resonate strongly with the themes explored in Goodley and Perryman’s (2022) essay Beyond the ‘Terrors of Performativity’: Dichotomies, Identities and Escaping the Panopticon, published in the London Review of Education. Reflecting on the enduring influence of Stephen J. Ball’s work on performativity in education, the authors examine the ways in which educators are shaped, and at times constrained, by systems of accountability and surveillance.

Like Claire, one of the authors, I inhabit a space where personal values and creative instincts are continuously mediated by the performative demands of institutional frameworks. Rather than experiencing this tension solely as limiting, I approach it as a generative friction, a prompt to reflect, reimagine, and re-author what it means to perform as both an educator and an artist within a culture focused on visibility and outcomes.

A line that particularly resonated with me describes how Ball’s writing “not only changed what a teacher did, but also who they were” (Goodley and Perryman, 2022, p. 3). This insight mirrors my experience, especially during the observed components of the PGCert, where teaching often felt like performing for an invisible audience. In those moments, the relational and improvisational nature of education gives way to a kind of staged competence. My concern is not only about being judged, but about unconsciously internalising the voice of the institution, echoing Claire’s reflection on being “ventriloquated” by dominant discourse (Goodley and Perryman, 2022, p. 7). I recognise this same displacement in photography, when an image begins to speak to someone else’s expectations rather than the artist’s original intent.

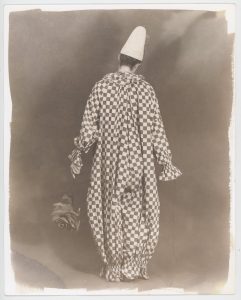

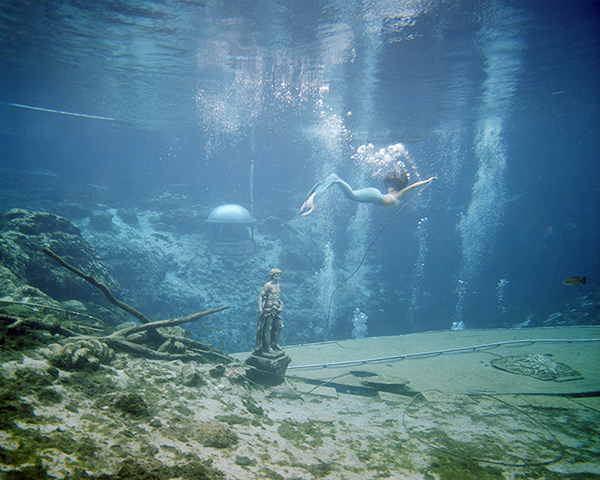

As a photographer, I have long been drawn to performance as both subject and method. My series Simulations investigates constructed identities and staged environments, interrogating the line between artifice and authenticity. In The Mermaid, Weeki Wachee Springs, the subject performs a role that is both spectacle and self-expression. The gaze is curated, yet remains personal. I see teaching in similar terms, as a layered, live performance in which visibility and vulnerability are closely entwined.

The Mermaid, Weeki Wachee Springs – from the series Simulations. 2018

Beyond the ‘Terrors of Performativity’ has offered both a critical and emotional lens through which to reflect on my own position. It serves as a mirror and a provocation, locating my practice within a wider conversation about power, creativity, and the layered complexities of educational life.

OBSERVATIONS

- Peer Observation / Max Ferguson observing Unit 3: Collaborative

- Tutor Observation / Tim observing Unit 3: Collaborative

- Observing Max Ferguson / BA Photography Year 1 Publication Unit

REFLECTION 4: Signature Pedagogies in Art & Design by Orr & Shreeve (2017)

Max Ferguson’s thoughtful observation of my Collaborative Unit session – and suggestion to read Signature Pedagogies in Art & Design by Orr & Shreeve (2017) – prompted me to spend time with this text… to reflect upon it and to relate it to my teaching practice. Max’s comment that the session space felt ‘like a boardroom, an office, or an agency’ also helped me realise that I had constructed a learning environment that mirrored a real-world context. Both Max & I come to teaching from extensive time in industry. We are both active photographers and both held roles as Photo Directors at internationally renowed publications for many years. I had aimed for the sessions of the Collaborative Unit option I run (D&AD New Blood Awards) – which includes students from 3 photography MA’s – to mirror industry. To feel relevant, energising and dynamic, but it was only after reading Signature Pedagogies in Art & Design by Orr and Shreeve (2017) that I truly began to understand the pedagogic significance of that approach.

Orr and Shreeve describe the studio not simply as a physical space, but as a ‘state of mind’ – a conceptual and pedagogic framework where risk-taking, collaboration and peer dialogue are central to learning (Orr & Shreeve, p. 91). This is a transformative idea for me. It gives theoretical grounding to my teaching instincts and clarifies how the professional practice sessions I design are, in essence, operating within the pedagogical framework of industry, even if they look and feel very different from traditional industry based teaching.

This understanding allowed me to view the Collaborative Unit sessions through a new lens… as a purposeful embodiment of what Orr & Shreeve (2017) define as signature pedagogy; a method through which students are encouraged to think, behave and reflect like creative professionals. The space, while non-traditional, became a kind of expanded studio: a simulated industry environment that maintained the values of experimentation, feedback, and community that define meaningful learning.

The most impactful realisation was understanding the value of blending my professional and academic identities. Orr & Shreeve challenge the notion of keeping these worlds separate; instead, they suggest the overlaps between practice and teaching are not only valid, but essential. This helped me embrace the fluidity of my role as a practitioner-educator and see my teaching as a direct extension of professional experience, not a separate or secondary activity.

In summary, Signature Pedagogies in Art & Design provided me with the language, theory, and critical perspective to better articulate and evaluate my teaching practice. It has turned instinct into intention and offered a richer understanding of how the learning environments I create, can be powerful, practice-informed pedagogical spaces.

CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1 – Knowing & Meeting the Needs of Diverse Learners

Case Study 2 – Planning and Teaching for Effective Learning

Case Study 3 – Assessing Learning and Exchanging Feedback

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Advance HE (n.d.) ‘Advance HE Scotland Thematic Series: Active Learning’. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/scotland/thematic-series/active-learning

- Atkins, A. (1843) Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. [No place of publication]: [Self-published].

- Atkins, A. (1843) Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. https://ttp.royalsociety.org/ttp/ttp.html?id=2f7d4394-8ec7-4833-b67d-a69b90040592&type=book&_ga=2.186359657.1115929948.1704188280-1209525634.1700154565

- Atkins, A. (1853) Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns. [No place of publication]: [Self-published]

- Brookfield, S.D., 2017. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated from French by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Goodley, C. and Perryman, J. (2022) Beyond the ‘terrors of performativity’: dichotomies, identities and escaping the panopticon. London Review of Education, 20(1), pp.1–14. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.20.1.29

- Hattie, J. and Timperley, H., 2007. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp.81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995) ‘Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy’, America. Educational Research Journal, 32(3), pp. 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Orr, S. and Shreeve, A. (2017) Art and Design Pedagogy in Higher Education: Knowledge, Values and Ambiguity in the Creative Curriculum. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group

- Orr, S. and Bloxham, S., 2013. Making judgements about students making judgements: the complexities of criteria. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(2), pp.232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.638901

- Perryman, J. (2006) ‘Panoptic performativity and school inspection regimes: disciplinary mechanisms and life under special measures’, Journal of Education Policy, 21(2), pp. 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930600566280

- Pope, T. and Benington, M. (2024) Almost Nothing But Blue Ground. Exhibition at FormaHQ, London, 8–19 April. Available at: https://forma.org.uk/projects/almost-nothing-but-blue-ground

- Sadler, D.R., 2013. Assuring academic achievement standards: From moderation to calibration. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(1), pp.5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2012.714742

- University of the Arts London (2023) Embedding framework: Climate, social and racial justice. Available at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0037/399376/Embedding-Framework-Climate,-Social-and-Racial-Justice.pdf

- University of the Arts London (2023) Student parenthood and caring support guidance. Available at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/414689/Student-parenthood-and-caring-support-guidance_v1a_11.2023.pdf

- University of the Arts London (n.d.) Teaching and learning. Available at: https://canvas.arts.ac.uk/sites/working-at-ual/SitePage/41410/teaching-and-learning

- Webb, D. (2018) Bolt-holes and breathing spaces in the system: On forms of academic resistance (or, can the university be a site of utopian possibility?) Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 40(2), pp. 96–118. doi:10.1080/10714413.2018.1442081

- Willcocks, J. and Mahon, K. (2023) ‘The potential of online object-based learning activities to support the teaching of intersectional environmentalism in art and design higher education’, Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 22(2), pp. 187–207. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1386/adch_00074